The Ukrainian strikes on Russian strategic bomber airbases may have used refurbished 1970s Soviet-designed Tu-141 remote-controlled drones.

Source: Tupolev Tu-141. (2022, December 8). In Wikipedia.

Background

The start of December has marked significant changes in the nature of Russian airstrikes in Ukraine, and of Ukrainian airstrikes into Russia. For both countries, the nature of the threat from the other side has changed. The capabilities (the military resources available) are evolving, as is the political will to use them. These shifts introduce a new phase in the conflict; one that will likely last throughout the winter as land operations become increasingly constrained by weather conditions.

Russian Airstrikes

Russian airstrikes into Ukrainian territory have been a defining component of this conflict. The Kremlin has launched many hundreds of ballistic and cruise missiles, and drone attacks at targets across Ukraine. But for several months now, Russia has been assessed to be running short of its most advanced (longest-range and most accurate) cruise missiles, such as the Kalibr ship-launched and Kh-101 air-launched systems. As of early December, Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov estimated that Russia had used 85 percent of its stock of Iskander ballistic missiles, and more than half of its pre-war stock of 500 Kalibrs and 300 Kh-101/555 cruise missiles. As long ago as June, Moscow started to use anti-ship missiles, such as Oniks, and surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) such as the S-300, in secondary modes against land targets.

In early September, the Kremlin’s campaign changed. Russia received around 1,000 Iranian Shahed-136 long-range drones, and military planners opted for fewer strikes but with a greater number of missiles in each wave, in part to counter Kyiv’s steadily improving SAM defenses, as larger concurrent packages of missiles make the defensive task harder. Moscow’s targeting also focused on Ukrainian power generation and distribution infrastructure. By the end of November, the national power company Ukrenergo said that around 40 percent of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure had been damaged. Each subsequent strike makes repair more difficult, and Ukraine has had to stop selling electricity to the EU, which was a valuable currency-earning export. On Nov. 23, the EU declared Russia to be a state sponsor of terrorism, as “the destruction of civilian infrastructure and other serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law amount to acts of terror.”

Since the start of the conflict in February, Kyiv has received a considerable number of air-defense systems from western countries, to add to their indigenous S-300. These include the US NASAMS, German IRIS-T, Norwegian Mistral, Spanish Hawk and Aspide, and French Crotale, as well as numerous shorter range and portable systems. Almost all these weapons are being used in combat for the first time. The biggest challenge, however, is integrating, layering, and coordinating these many systems for optimum effect; in the latest Russian airstrikes, Kyiv claims to have shot down 60 out of 70 missiles fired, which indicates that this challenge is being met. President Volodymyr Zelensky has requested deliveries of the US Patriot and Israeli Iron Dome systems, but to date these have not been granted. Kyiv has also been successful in a key element of self-defense, which is “OPSEC” (operational security), by suppressing reports, such as government statements, by journalists, or on social media, about the exact location of missile strikes or the damage inflicted. This, added to Russia’s relatively poor tactical intelligence, has compounded Russia’s inability to accurately select and prosecute targets.

In what may be a combination of a shortage of land-attack missiles and an effort to overwhelm the capable Ukrainian air defenses, as of late November Moscow has further adapted its tactics to include firing older Kh-55 missiles with their nuclear warheads removed, and by increasing the number of different directions (from further north and further south, as well as east), from which the missiles are vectored. On Dec. 6, Kyrylo Budanov, the head of Ukraine's Intelligence Directorate, stated that recently downed cruise missiles had only been assembled within the last two months, which provides further evidence of reduced stockpiles.

Ukrainian Airstrikes

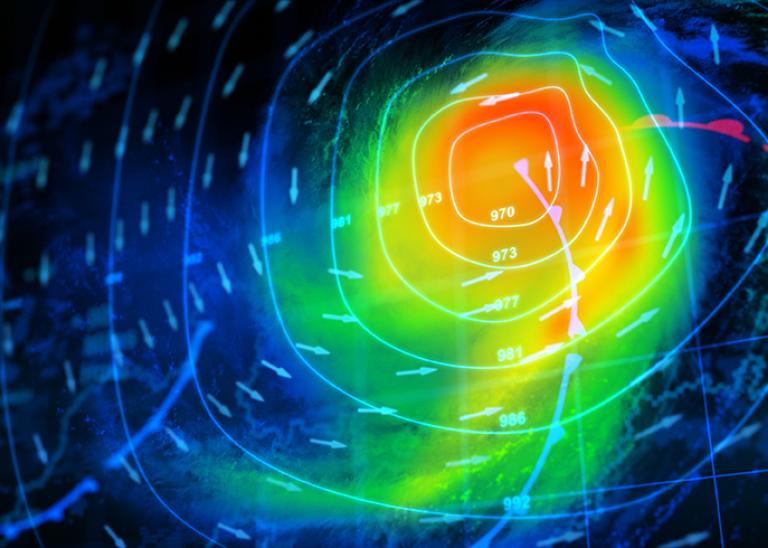

In recent days, explosions have been reported in four “deep strike” locations in Russia. On Dec. 5, drones targeted Engels airfield in Saratov Oblast and Dyagilevo airfield near Ryazan. These are both operating bases for the Russian Air Force strategic bombers, including the Tu-95MS that are used to launch Kh-42 and Kh-101/Kh-555 cruise missiles. The fact that these airfields were 500 and 450 km (315 and 285 miles) respectively from Ukrainian territory, and were high-value operational bases, indicates both a marked step up in Kyiv’s strike capability and significant failings in Russian air-defenses. The following day, an explosion was reported at an oil storage facility at the Kursk-Vostochny Airport, and two drones reportedly struck empty diesel fuel tanks at the Slava oil plant in the town of Surazh, Bryansk Oblast. These locations are around 80 kilometers (50 miles) inside Russian territory. Russian officials blamed the strikes on Ukrainian drones but, as with previous incidents on Russian territory, authorities in Kyiv maintain a deliberate ambiguity and have not claimed responsibility.

These four incidents represent a new phase in Ukrainian operations, in attacking targets in Russia. Previously, the Russian city of Belgorod has been regularly damaged by artillery, but it is effectively within the line of contact for land troops. An explosion in the port of Novorossiyisk, on Nov. 17, was unusual as it was considered beyond the range of Ukrainian missiles or drones. Earlier Ukrainian long-range strikes on airfield and naval base targets in Russia-annexed Crimea had also exposed significant shortcomings in Russian surveillance and self-defense.

There are two theories for the long-range strikes into Russia of recent days. Russian authorities have claimed that Ukraine is using Cold War-era Tu-141 drones, which have the necessary range but not necessarily the reliable accuracy. Ukrainian authorities have also released hints over the last two months that they are developing a long-range drone. The Turkish Bayraktar TB-2, which Kyiv used to significant operational effect in the early stages of the conflict, only has an operating range of around 150 kilometers (95 miles). The recent strikes could have involved one or both of a refurbished older drone or a new development. In either case, it is not known how many Ukraine possesses, their production capacity, or what their capabilities are.

The relatively light damage caused by these incidents is less important than their strategic impact. They will affect Russian military calculations, forcing a new concern over long-range strikes and the vulnerability of assets. Tactically, it may force the Russian Air Force to redeploy its aircraft, imposing an increased logistic and operational penalty. The Kremlin will have noted that Moscow is within the strike radius of these long-range drones, whether or not they believe that Kyiv would consider the capital a valid target.

Outlook

As the land offensive and counter-offensive increasingly stagnate over the winter months, it is likely that attention will focus on the impact of long-range airstrikes. Evidence indicates that Russia is short of its modern, longer-range cruise missiles. It will increasingly rely on re-purposed older or anti-ship missiles, newly produced missiles (and likely seeking to evade sanctions to source semi-conductors), and further imports of drones from Iran and other countries. Meanwhile, Ukraine will continue to strengthen its air defenses, while requesting increasingly capable systems such as Patriot and Iron Dome.

The Ukrainian airstrikes of Dec. 5-6, with long-range attacks on strategic Russian military targets, will likely continue. Kyiv will doubtless select targets carefully to avoid collateral civilian damage, in order to maintain its international support, and its legal justification of self-defense. Ukraine has repeatedly exposed Russian shortcomings in its situational awareness and self-defense: the Kremlin may react with senior military dismissals and a concerted effort to better counter this new threat.

Kyiv’s targeting of military infrastructure within Russia may influence policy among donor countries, such as the US. Currently the US has not supplied Ukraine with longer-range weapons systems (such as ATACMS) in part because of their ability to reach into Russia and the concern of consequent escalation. If Ukraine consistently strikes valid military targets accurately and avoids collateral casualties, then the US may relent.

It is also worth noting that with Russia’s massed long-range airstrikes, and with complex long-range SAM engagements, collateral damage is inevitable. A proportion of missiles will experience guidance errors or may be affected by electronic jamming. Despite satellite navigation, some weapons will miss their targets. SAMs may miss their targets or be jammed by countermeasures. Debris from successful engagements may cause collateral damage. On Nov. 15, a Ukrainian SAM landed in Poland killing two people, and on Dec. 5 missile remnants landed in Moldova. Incidents such as these are likely to continue: the proximity of Belarus means that it is also vulnerable to a similar accidental overflight.

Airstrikes are a form of coercion. Russia does not have sufficient offensive capability to destroy Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, and Ukraine does not have enough long-range drones to neutralize Russian strategic bombers. The key effects in both cases will be the impact on the morale of the civilian population, and on leadership and military-decision making of the two sides.

Crisis24 provides in-depth intelligence, planning, and training, as well as swift and actionable responses to keep your organization ahead of emerging risks. Contact us to learn more.

Author(s)

Chris Clough

Intelligence Analyst IV, France

Chris Clough joined Crisis24 in May 2022 after a career in the UK Royal Navy and a period as an independent consultant. He was previously the Naval Attaché to France (2013-16) and the Head of the...

Learn More