President Erdogan has increasingly used the military to support his government’s maritime expansion and energy exploration.

There is an old Turkish saying that goes, “the Turk has no friend but the Turk.” As the country drifts further away from its once central foreign policy of “zero problems with neighbors” in pursuit of regional dominance, the proverb rings increasingly true.

The reorientation of Turkey's foreign policy has led to many of its geopolitical friendships crumbling. The reorientation also comes at an important juncture in Turkish politics as the domestic scene is marred by an escalating economic crisis and a fierce crackdown on any opposition to the long-term incumbent Justice and Development Party (AKP). Correspondingly is the increasingly 'Neo-Ottoman' administration of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose fate lies in the hands of the Turkish public as they prepare to head to the voting booths in June 2023.

The country’s shift in foreign policy objectives is driven by internal and external factors. Domestic politics has long been riven by political, religious, and ethno-nationalist divisions. The most alarming domestic factor contributing to the increasingly polarized political scene is the current economic situation. The plunging value of the Turkish lira against the US dollar, the highest inflation rates since 1998, and rising loan defaults have spurred dissatisfaction amongst the Turks, many of whom look to their President for salvation. After failing to stop the downward economic spiral, Erdogan has employed other measures to cling to power: periodic crackdowns on opposition parties; harsh rhetoric directed toward Eastern Mediterranean rivals amid the push for hydrocarbons; military expansion and adventurism; and entering unorthodox alliances to strengthen the country’s geopolitical position. This was not always the case, as the AKP’s initial foreign policy was one of cooperation and interdependence.

Zero Problems with Neighbors

The “zero problems with neighbors” policy was introduced in 2004 by then-Chief Advisor Ahmet Davutoglu. The new policy was aimed at desecuritizing Ankara’s foreign policy discourse in favor of regional economic cooperation and interdependence over regional competition. This policy is also reflected in Turkey’s NATO-membership and lengthy EU-accession process, which have been adversely impacted by the AKP’s pursuit of regional dominance.

The US’ long-term presence in Iraq created favorable conditions for the implementation of Turkey’s zero problems with neighbors policy; regional support systems were of the utmost importance. However, the US’ military drawback from Iraq created a new power configuration in the region. Tensions rose when the AKP’s popularity started to decline in 2015, along with failed negotiations with Kurdish militants. The US’ disengagement from the region has made Turkey’s neighbors more reactive rather than receptive of Turkish policies in recent years, exacerbating the shift in foreign policy.

Shifting Foreign Policy

This shift in foreign policy can also be understood as Neo-Ottomanism; an irredentist and imperialist Turkish political ideology that aims to reinvigorate Turkey’s influence in the Middle East and the broader Turkic world. Successful pursuit of this policy would make Ankara the pre-eminent powerhouse in the region. The term has become synonymous with AKP-rule as members have often referred to both their leader and supporters as Osmanli torunu (descendant of the Ottomans). Under the AKP’s rule, the country’s transformation from a parliamentary system into a presidential one echoes the strong and centralized leadership of the Ottoman era, further cementing the ominous return to Ottoman era political strategy.

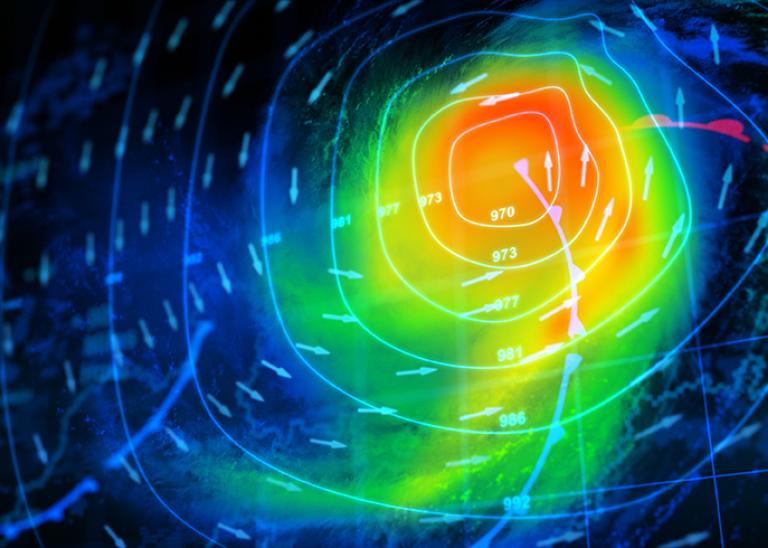

More recently, the revival of the ‘Blue Homeland’ strategy – a colloquialism for Ankara’s maritime claims and energy exploration efforts in the Eastern Mediterranean – has accelerated the AKP’s ‘Neo-Ottoman’ foreign policy. In its pursuit, Turkey has clashed with competing interests from Greece and Cyprus. The resultant diplomatic tensions are occasionally exacerbated by belligerent naval activity. In lieu of the Blue Homeland strategy, Turkish and Azerbaijani special forces simulated an attack on Greek islands in late May, drawing a sharp rebuke from Athens.

The recent and ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine has further cemented Erdogan’s long-running double game in which Turkey plays Russia against the West; delivering combat drones to Kyiv whilst ignoring international sanctions against Moscow; taking delivery of the Russian S-400 air defense system amid NATO objections, but ultimately deciding not to switch it on likely in exchange for concessions from the West. This double game is also evident in Turkey’s repeated threats against Kurdish separatists in northern Syria; it is as much about flexing their military superiority over these separatists and the Syrian government as it is about drawing on tensions between Russia and the US, using Syria as a proxy battleground.

Once again harking back to the Ottoman era, Turkish leadership is openly seeking to expand Ankara’s influence in the Turkic world, through trade, investment, shared culture, and military assistance. While largely an outlay of soft power, Turkey has used its growing military-industrial base to further relations with its neighbors, most notably Azerbaijan. Turkey maintains a small military presence in the country in recognition of the outsize role Ankara played in supplying and supporting Baku during the 2020 Second Karabakh War. At recent events to mark Azerbaijani Independence Day, Erdogan solidified Turkey’s allegiance with Baku with remarks about the two countries’ shared fate and brotherly bond.

Looking Forward

With the Presidential and parliamentary elections creeping closer, this shift in foreign policy, the resulting retreat from international relations, and the country’s involvement in various conflicts in the Eastern Mediterranean and the wider region will undoubtedly influence the country’s short- to medium-term political scene. The Turkish economic crisis has led to increasing dissatisfaction with the incumbent AKP; as illustrated in the 2019 local elections in which the party lost control of the key cities of Istanbul and Ankara.

A pre-election crackdown targeting opposition parties, most notably the CHP, has accelerated in recent months as the head of the CHP’s Istanbul wing Canan Kaftancioglu was banned from politics and sentenced to at least five years in prison for insulting AKP officials. Istanbul mayor Ekrem Imamoglu (CHP) is currently being investigated on the same counts and awaits the verdict Imamoglu’s 2019 mayoral victory marked the first time the AKP and its Islamist predecessor had lost in Turkey’s biggest city in 25 years. The reversal may signal the beginning of the end for the AKP and Erdogan, who has been in power since 2014. The AKP’s popularity is declining, and they are willing to take increasingly unconstitutional measures to retain power, as well as adopt increasingly populist policies such as the Blue Homeland policy in order to appeal to their voter base. This is particularly true at a time when they are less able to affect domestic change.

Crisis24 provides in-depth intelligence, planning, and training, as well as swift and actionable responses to keep your organization ahead of emerging risks. Contact us to learn more.

Author(s)

Eunèt Louw

Intelligence Analyst

Eunet is an analyst for Crisis24's Response Coordinator Operations Center and supports PRISM for the Embedded Intelligence Services team. She studied Political Risk at Stellenbosch University...

Learn More